- Home

- Catherine Butler

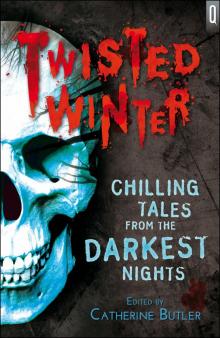

Twisted Winter Page 3

Twisted Winter Read online

Page 3

“You are not a gentleman,” Mrs Wallace said.

“Perhaps not,” said Julian. “But I’m an excellent businessman.”

Mrs Wallace gazed into the slits in the bulbous green froggy eyes of his mask, for a long moment.

She said, “You are. And luckily, so is a friend of mine.”

She raised her brilliant fantastical mask to cover her face again, and turned, and in the same instant the room fell silent, because once more the Harlequins stopped playing.

“Aaaaaaw,” said the children, who had been enjoying their cavorting. But the two Harlequins each gave them a little bow and followed Mrs Wallace, who was sweeping towards the front door.

Mr Macaulay, stationed near the coat-rack, helped to drape her heavy silk cloak round her shoulders, and she smiled at him. Then she left, as the Harlequins opened the front door, and they all went away past the marble columns, down the marble steps.

Out of the crowd of dancers came the man in the appalling mask, following them. “Thank you!” he called to the witch-face of Ruth Ransom, as he seized his hooded cloak from the rack. “Lovely party! Happy Hallowe’en!”

Julian Hogg had tried unsuccessfully to follow Mrs Wallace; he was standing beside the front door, in his green velvet jacket and his half-frog face. He put out a hand towards the man in the mask as he went by.

“I don’t believe we were ever introduced,” Julian Hogg said.

“Just a friend of Mrs Wallace’s,” the man in the mask said. “A very old friend. A business friend, you might say.”

He loped down the white marble steps into the darkness, and paused. Then he turned his head back toward Julian and the house, so that the light caught the appalling, immobile, vicious mask with the two bleeding stubs on its forehead. Julian found himself suddenly giddy, and he felt his fingers curl in against their palms, rubbing softly, as if they could still feel the greasy olives that might, or might not, really have been eyeballs. Somewhere in the night, or perhaps in his mind, he heard a thin high call like the note of a hunter’s horn.

Still facing him, the man in the mask reached to the dangling straps behind his neck and pulled his mask away.

Nobody but Julian Hogg was there to see that the mask had been simply a copy of the dreadful face that was underneath. And the monstrosity of the real face was far more appalling because it was alive: now the glaring yellow eyes blinked, the twisted mouth moved its dark lips. For an instant Julian stared in horror at the terrifying malevolent sneer, and the stubs of horns dripping blood.

Mrs Wallace’s old friend smiled at Julian. The smile was the worst thing of all.

“See you soon, Mr Hogg,” he said.

Then he turned, and was gone.

The Gates

Liz Williams

I didn’t like our new home, but my mum said that it would grow on me. I wasn’t sure about that. I thought that it was too flat, the hills a distant blur of blue. The village lay low and soggy. The grass in between the apple trees was puddled with wet and not only after it rained. It was late November now and everything was brown and grey. The trees looked as though someone had taken a black pen and drawn them against the sky. They were alder and willow and ash, Mum told me, and in the spring a man would go around with a machine and give the willows a haircut, until they looked like the ugly heads of old bald men. This was because willow grows too fast, she said.

“How do you know?” I asked her.

“Because I lived near here when I was a little girl, like you, Hannah. A bit younger, maybe – I was only ten when we moved away. I lived with my grandmother, your great-grandmother. She had a cottage in a village called Oddmore, which is on the other side of Taunton.”

“Does she still live there?” I was curious. I hadn’t known my nan, let alone a great-grandmother.

“No, she died years ago.”

“Why did you live with her?”

“Because my mother couldn’t look after me and then she died, too.”

“Why couldn’t she look after you?”

“She was ill.”

“What was the matter with her?”

My mother sighed. “She had a problem with drinking.”

“Oh.” It was the first time we’d had this sort of conversation. I suppose it meant that I was old enough to understand, but I wasn’t sure I liked that. “Did you like it there?”

“Yes, after a bit. At first I didn’t. I thought the village was too small and nothing ever happened, especially after London, although we didn’t live in a very nice part of the city. But there was a lot going on. I suppose these days you’d say I was a street kid.”

“It’s not like Bristol, either. Here, I mean.”

“No, it’s not, but you’ll get used to it. It’s a different kind of life.”

I suppose it had worked before, for my mum, so she thought it might work again. But I was not sure that I would come to like it. The village was not a pretty one, but built of mainly modern houses. Ours was older, a proper cottage, but it was also damp and there were slugs in the kitchen in the mornings. Mum said they crawled up the pipe. I had to go to school on the bus but it was nearly the end of term and everyone already had their own friends. And they were all white: only one other girl was like me. I got tired of explaining that my dad’s dad had been Jamaican, although actually they weren’t horrible about it, just didn’t seem to really get it.

So at the weekends I moped about the house, and eventually, on the third Sunday, my mother told me to go out and get some fresh air.

“You’re always on that computer.”

“I like the computer. I’ve got tons of friends on Facebook. And I’ve got to do my homework.”

My mum looked amused. “You’re not usually so keen on your homework.”

“But Mum, this is for history. It’s about the ancient Egyptians.” I fingered the looped cross around my neck. My ankh: I never took it off. Sometimes I thought it was an anchor, as well an ankh. Linking me back to the past. My dad had left it with my mum when I was a baby, for me. It was silver. And Dad had loved anything to do with Egypt, she’d told me. He saw it as part of his ancestry: even though my grandad’s family had come from Jamaica, the Egyptians had been a great African civilisation, he’d said. So I felt that the ankh was my link to him.

But it was no use protesting. I put on some wellingtons and went out through the gate into the orchard, and puddled about in the wet grass. There were apples, but something had chewed holes in them and they smelled cidery, which I didn’t like. I went through the orchard, and found that the end of it led onto a field. There was a small brown pony, so I walked down the slope towards it and the long line of bushes at the bottom of the field. When I looked back, I was surprised at how invisible the village had become: I’d thought that all the houses and their gardens went back much further, but it was like being in the middle of nowhere. The bushes had long black thorns like iron nails and I didn’t want to get too close. When I reached the place where the pony had been, it had gone.

I looked around. There was a hollow in the bushes. I thought the pony must shelter underneath them, so I ducked under and saw the pony some distance away, making its way through the maze of bushes without any hurry. At the bottom of the hill was a trickle of a stream only a few feet wide. I could follow it, I thought.

I could be an explorer.

Sometimes, I thought my dad was an explorer. Like Indiana Jones, in my mum’s old movies. Off in the rainforest somewhere, talking to jaguars, or finding his way through a pyramid, looking for treasure. But inside I knew where my dad was: in the ground, long gone. My mum had said it was cancer but it wasn’t. I’d found his certificate, which they give you when you die, and it said overdose. But it made me think all the more of my mum, that she’d tried to protect me, that it had been a struggle. My dad and my nan. It was the same thing, really.

The stream was winding, twisting through the thorn bushes. After a while, the thorn trees grew less thickly and after I’d climbed ov

er a broken barbed wire fence, I came out into a small, bare valley, with slopes where the sheep had cropped the grass and gorse growing on the hill like sunlight. I kept following the stream, but I kept an eye on the sun, too, like a proper explorer would: it floated through the clouds like a ten pence piece. At one point, I climbed the hill, which wasn’t really a hill, but just the slope of a field, and looked back; I saw the tower of the village church and I knew that as long as I could see it, I could find my way home.

Twenty minutes later and I could hear water. It was not like the trickle of the stream, but a steady rushing noise and it puzzled me: surely the hills were not steep enough for a waterfall? Then I came around a bend and saw that it was what’s called a sluice. The stream was channelled, it poured through a gate like water out of a kettle into a much wider stream. Except that it wasn’t a stream, really, but a canal: maybe fifteen feet wide, and very still. Past the place where the water flowed in, which was foamy and white, the canal looked like oil. The slope of the fields tailed off onto flat land, banked by willows. There was a path, but it was marshy and reedy, with the tall bulrushes like spears all along it.

So I followed the path. There was something about the canal, but I couldn’t say what it was. I didn’t like it and yet I did, at the same time, as though it was pulling me on. I couldn’t help thinking about where it would end – maybe at the sea, although later I thought that this was stupid. It would probably join up with a river.

I walked for about an hour. I couldn’t seem to stop, as though my legs were mechanically taking me forward like a machine, and I sang as I walked: it was a song that my dad had written for me. As far as I knew it was the only thing he’d left – that, my name, and the ankh of course.

Hannah and roses, Hannah and flames,

Whatever who knows is, Hannah’s my name…

That’s how it began, and maybe it was silly, but it kept me going.

I’d never walked so far before, even though I’d been used to walking up one hill and down the other and up again in hilly Bristol, there and back to school. But this was different: flat, and the canal didn’t really change much, until I came to the gates.

When I saw them, I slowed down. At first, from far away, they appeared as a small black patch at the end of the canal. When I drew a bit closer, they looked like a doorway into the sky. They were huge, made of black metal, and they reared up above the motionless water of the canal. I could see some sort of mechanism – a wheel – set into the side of the gates, and probably this opened them. It did not look as if it had been moved for years. It looked painted shut, not rusty, just thick with black paint so that it shone, even though the sun was covered by the clouds.

I stood for a long time and looked at the gates. There didn’t seem to be any way around them, unless you climbed up the bank, which was quite steep. I listened, but I couldn’t hear any traffic, although there must be roads somewhere: I thought I was near Highbridge and that wasn’t far from the M5: you could hear the motorway from a long way away. Maybe it was so still because it was a Sunday.

A twig snapped and I turned. There was a man standing behind me. He made me jump, and for a moment, my heart banged in my chest. But he was old. He had a walking stick and in the brambles was a little old dog like a piece of a hearthrug. He had come down the slope: now that I looked more closely, I could see a tiny path.

“Afternoon,” he said. He sounded quite posh, like a retired teacher.

“I was looking at the gates,” I said.

“The King’s Drain.”

“Sorry?”

“It’s called the King’s Drain. It’s a sluice. Do you know what that is, young lady?”

“Yes. They explained it in school. It’s like a gate for keeping water in and out.”

He looked pleased. “That’s right. This one lets the water out at Highbridge. If there’s a high tide, though, they close the gates, because otherwise too much water will come in from the sea and flood up.”

“I saw a flood,” I said. “When we came here from Bristol. It was all over the road.”

He nodded. “Yes, that happens, sometimes. Most of this land is below sea level. That’s why it’s called ‘Somerset’. Before they put in all these drains and gates, it was flooded all winter – you could only graze cattle in the summer, you see, so it was called the ‘summer country’.”

That made sense. “That’s interesting,” I said.

He waved the stick at the gates. “They’re important, those. Keep the sea back. Well, I’d better be getting along or my wife will be wondering where I’ve got to.”

He gave me the polite smile that some grownups give to kids and called the dog on. I waited until he had gone further down the path and then I saw him cut up through another little path and disappear. It wasn’t that I hadn’t trusted him, actually, but I felt like being on my own. I didn’t want to leave the gates, but then it struck me that it would get dark soon and I didn’t like the thought of being on the towpath when I couldn’t see. So I went back, walking quickly and singing my dad’s song under my breath, along the canal, and the stream, and the field. I could feel the gates all the way, though, over my shoulder. It didn’t seem nearly as long on the way back: it doesn’t, if you’ve walked somewhere twice, I’ve noticed.

“Did you have a nice time?” my mum said, when I got in. “I was a bit worried. You were ages.”

“Yes. I went for a walk. But I took my phone.” I showed her.

“Where did you go?”

“Along the canal. I met a man who told me about the sluice at the end.”

She looked vague. “Oh, is there a sluice? I’d forgotten about the canal. It’s only a little one.”

“It’s called the King’s Drain.”

“I can’t remember which king it would have been.”

“He said it was to hold the sea back.”

And it was. But not just the sea.

* * *

That night, I woke up. I don’t know what woke me. But my heart was banging against my ribs again, and I felt light, as though I wasn’t real any more. I knew I had to go back to the gates.

Going out at night on my own was stupid, I know that. But it didn’t feel as though I had a choice. I dressed, and then I let myself out of the back door and ran through the orchard, and down the field, and into the thorns.

There was a full moon and the sky was full of stars. I hadn’t realised that there were so many. In Bristol, the sky is orange because of all the streetlights and you can only see a few, but now there were thousands of them. The moonlight cast sharp shadows; the thorn trees were blue and black. I’d been feeling a bit scared but now I was excited: it was like being out in a secret world, that no-one else ever saw.

Soon, I was at the canal. The light from the moon lay along the water like a path, a silver road, and the gates were at the end, but much bigger than they actually were, really huge, like a castle. I was still excited, but afraid, too, and I told myself I had to be brave. I followed the moon path, until the black gates loomed up in front of me and then I had to stop.

The light fell on the big wheel so that it was silver, too.

Open the gates. The voice was in my head; maybe I was going mad. But the thought didn’t bother me.

“I don’t know how.”

The wheel will open the gates.

There was a ledge, on which someone could stand to turn the wheel. So I hopped onto the ledge and put my hands on it. I had forgotten to bring gloves and the metal was frosty cold. It hurt my hands, but to my surprise the wheel span easily, really quickly, as though the slightest touch would send it whirling. I lifted my hands and the wheel spun until it was round like the moon and the gates began to open. I jumped down from the ledge.

Within the gates, everything was black. I couldn’t see the canal, or anything beyond and now I was really scared.

Go inside.

“I don’t want to.”

You must. And I felt my feet taking me forwards into the

blackness.

As I did so, however, I saw that there was a tiny light, a little spark like a candle. It was as though there was a very small figure, carrying a tiny lantern, walking towards me.

“Who’s there?”

No answer.

“Who is it?” My voice sounded very small, too. Then the lantern flamed up and someone was standing in front of me, man-height. His skin shone in the light from the lantern and it was like the old mahogany chest of drawers that my mother had in her bedroom, whenever she polished it. There was a black cotton cloth around his hips and the gleam of gold. When I looked up, I saw that he had a dog’s head, like a Dobermann: long and dark-furred. His eyes had a little spark. I ought to have run screaming but all the fear drained away from me, as if out of a sluice.

“Who are you?” I said. But I knew. Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead. The one who guides souls home.

“They’re waiting for you,” he said. I don’t know how he spoke, out of that dog’s face, but he did. It was the voice which had been talking to me. Without waiting, he turned as if he expected me to follow him and walked into the darkness. So I did.

I think there was water, still, but I couldn’t be sure. We walked for a short distance and sometimes it was as though the walls were metal, like bronze, and sometimes they were stone. At last the man with the dog’s head turned and said, “We are here. Do not speak unless someone speaks to you. And tell the truth.”

“Okay.” I wasn’t going to argue. I saw another door beyond his shoulder and then he opened it and guided me through.

I don’t remember a lot about the place beyond that. It was high, like a big cathedral, and it would have been dark except that it was lit by torches along the walls. There were people sitting on enormous stone thrones and I couldn’t see any of them clearly, but their skin was different colours – I don’t mean white or black or mixed like me, except for the dog-headed man, but blue and green and red, as if a child had coloured them in. They looked Egyptian, too: I knew they were gods, but the thought was too big to handle.

Twisted Winter

Twisted Winter